During 1980s the emphasis on the ideological transformation of the Somali state mattered to IMF more than sound fiscal policies did

Mogadishu (PP Editorial) — Active International Monetary Fund engagement with Somalia dates back to the 1980s, when Somalia embraced the Structural Adjustment Program. Tough negotiations preceded SAP whose stepping stone into influencing and directing the Somali economy was followed by economic liberalisation.

The year 1986 was supposed to usher in the unveiling of a national development plan. Instead, the former military government of Somalia began to implement SAP programmes. The mandatory SAP policies included reduction of public spending, jettisoning the centrally planned economy based on “scientific socialism”, and the devaluation of the Somali shilling.

Those policies resulted in inflation following the auctioning of hard currency that forced traders to hoard their commodities when price increases adjusted to the new official exchange rate angered the Minister of Finance Abdirahman Jama Barre, who ordered the police to force traders to sell commodities at prices before currency auction.

The education sector had had to adapt to the new SAP-mediated reforms by demanding fees from parents to subsidise teachers’ salaries. This phase of SAP is the least-discussed impact of the policies of the military regime that introduced a hybrid educational system funded through tax and fees from parents due to budget cuts to satisfy IMF demands.

The transition from state-controlled economy to state-directed market economy was not smooth. The rate of business start-ups was high, thanks in part to a business-friendly policy and the new investment law and the policy to encourage civil servants to become cash crop farmers. Lax public finance auditing had caused a surge in embezzlement of public funds, seen by many people then as the quickest way to make money illegally. The emphasis on state ideological transformation mattered to IMF more than sound fiscal policies did at a time when Somalia was one of the African countries affected by Cold War rivalries.

Whatever merits SAP would have had the hand of the state that negotiated and guided policies had determined its outcomes. Before SAP, IMF conducted a study on the discontinued franco-valuta, and concluded that the discontinuation caused inflation. Writing in the Industrial Management Review, a Unido-supported publication of the Ministry of Industries, a Somali economist noted that the IMF had made an analytic error: deflation was at work.

Renewed IMF engagement with Somalia may be derailed by similar mistakes — a corrupt government, lack of attention to detail on the IMf’s part or ideological emphasis.

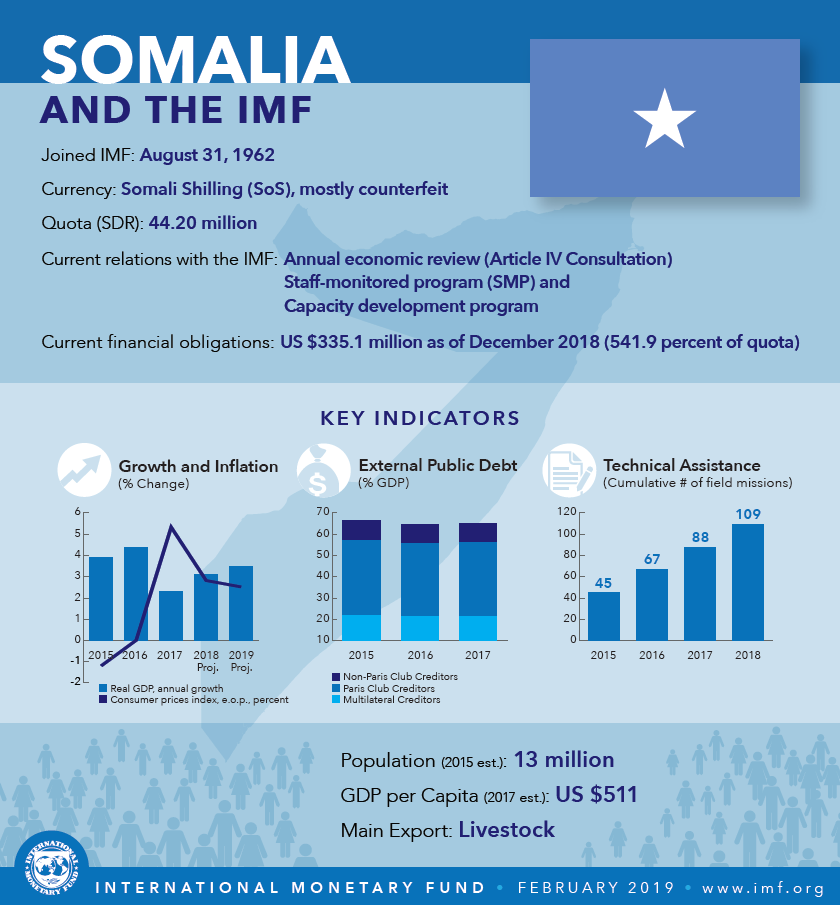

Since 2018 Somalia has made progress towards debt relief partly because of the oversight of the Financial Governance Committee and auditing practices adopted by the Federal Government of Somalia. Several factors can, if left unaddressed, derail the IMF Somalia programme.

1. Contradictory economic policies

If the pre-1991 IMF engagement with Somalia is any guide, the post-conflict economic policies, of which the debt relief is the most important, could be put at risk by divergence between the government policy and IMF priorities.

IMF shareholders wield much influence on state-building initiatives in Somalia. If the IMF places an emphasis on national interests of key shareholders (USA, UK, and several EU member states), Somalia will not have benefited from the debt relief. Somalia is dependent on African peacekeeping forces. The rush to sign resource-related agreements will shortchange Somalia, as shown by the recent illegal production sharing agreement signed by the Petroleum Minister with Coastline Exploration Ltd, as well as the decision not to include data on fishing licences (granted by the federal government) in the annual report of the Office of the Auditor General.

2. Inadequate audit regime at Federal Member States

Auditing inadequacies at Federal Member States pose a threat to the benefits Somalia could reap from Special Drawing Rights. Several Federal Member States have awarded fishing licences to foreign companies. How Federal Member States spend proceeds from fishing licences is unclear. Some national ports are run by a foreign parastatal, although the Federal Government of Somalia rejected “illegal” agreements under which DP World runs two Somali ports.

3. Marginalisation of politically minority Somali clans

Under the 4.5 power-sharing system certain Somali clans face political and economic discrimination. Clans such as Banaadiri and Jareer Weyn are subsumed into the 0.50 group of the 4.5 system. In Somalia, the term ‘political minority’ was invented after 1990, when clan-based armed militias became a feature of Somalia politics. Neither Banaadiri nor Jareer Weyn was classed as a political minority in pre-1991 Somalia. The violent reconfiguration of the Somali political identity gives primacy to four politically powerful Somali clans. The IMF ought to devise a policy that prevents its programmes from deepening inequality and political injustice.

For the IMF Somalia Programme to succeed, it would be worthwhile to include the three metrics outlined above in its metrics to ensure that IMF endeavours do not become intentionally quixotic assistance for the post-conflict economy of a fragile state.

© Puntland Post, 2022